Basic HTML Version

www.geotechnicalnews.com

Geotechnical News • March 2013

35

GROUNDWATER

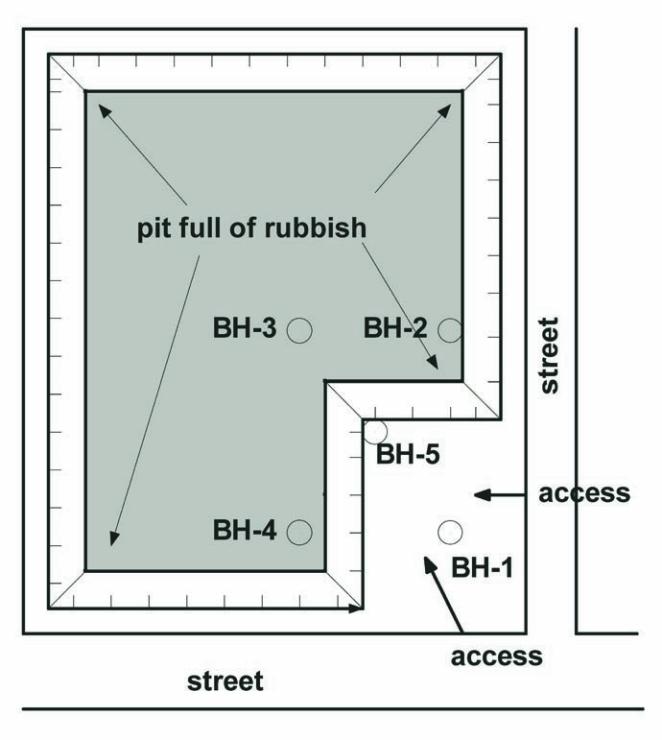

Figure 2. Sketch of the excavation: plan view of the hidden pit full of

rubbish.

were not as severe as nowadays. Yet,

the incurred extra expenses were

unexpected and significant. For the

engineering company, it meant that

their fees had to be increased because

the cost of the project was increased.

Dispute and settlement

The contractor threatened to sue the

owners, who threatened to sue the

geotechnical company. The consulting

engineer threatened to sue the geo-

technical company, but took care to

not threaten the owners. The discus-

sion between the three parties and

their attorneys quickly progressed, but

without informing or calling upon the

professional liability insurance. Dur-

ing the first meeting, the head of the

geotechnical company acknowledged

that only BH-1 and -5 were real, the

three other BHs being hypothetical.

Considering the similarity of initial

results (stratigraphy, nature of soils,

compactness, and water table posi-

tion), the geotechnical company had

decided to fabricate the logs of the last

3 BHs, based on the results of the first

two BHs.

The debate about the incurred costs

was especially interesting. The

attorney of the geotechnical company

made it clear that, whatever his client

had done, the dump was real. There-

fore, even if the owners had known its

presence before hiring the contractor,

the rubbish had to be excavated, and

replaced with an acceptable com-

pacted backfill. At the end of the first

meeting, the confusion and embarrass-

ment were palpable.

During the second meeting, the discus-

sion focused on the delays due to lack

of preparation, increased financial

needs to negotiate with the bank and

related extra costs, etc. After that, a

confidential agreement was reached

between the three parties at a third and

final meeting.

Conclusion

This case history teaches us a few

things. First, unprofessional work

may be kept secret. Here, it received

a financial penalty, in private, but this

did not harm the professional’s stand-

ing. Next, since the professional never

called upon his professional liability

insurance, one may infer that the

unprofessional work never produced

an increased premium. Finally, since

both the case and its settlement never

went public, as they would have

in court, the professional order or

corporation was kept unaware of the

situation. This is a negative aspect of

the confidentiality rules, which work

against the order or corporation’s man-

date to protect the public.

References

Chapuis R.P. 2010. Using a leak-

ing pool for a huge falling–head

permeability test. Engineering

Geology, 114(1–2): 65–70.