Geotechnical News December 2011

63

THE GROUTLINE

place or permeate. In such instances,

the hole spacing must be close enough

to permit overlap of grout injection be-

tween holes.

The orientation of grout holes should

be selected to maximize the intersec-

tion of karst zones. This may involve

steeply angled holes where steeply

dipping or vertical features are pres-

ent or vertical holes, where horizontal

or horizontally connected features are

present. Grout holes should be orient-

ed across faulted zones or other areas

within a project site where additional

karst features would be expected.

The materials and methodology of

grouting can be selected based on eco-

nomics and performance. The effects

of groundwater, where present, must be

considered to prevent dilution and loss

of grout effectiveness. A limited mo-

bility grout should be selected where

displacement and/or compaction of

sediments is required, or where it is de-

sirable to limit filling voids to specific

areas without significant lateral spread

of the grout. For very large voids, grav-

ity filling with a concrete mix may

be appropriate followed by second-

ary grouting with a finer or more fluid

grout mix to seal remaining openings.

The key in successful planning is

to anticipate variability. Even though

large interconnected voids may not

have been encountered, it is essential to

have a plan to address them whenever

grouting in karst. Identify volume alert

levels so that the grouting plan may be

changed to limit the loss of large vol-

umes of grout. If grouting with a high

mobility grout, be prepared to change

to a limited mobility grout or other ap-

propriate method, should an unantici-

pated large take occur.

Managing the Drilling

The drilling should be used as an

investigative tool as well as a means to

make grout injections. All holes should

be logged and evaluated to verify that

conditions are as anticipated and are

appropriate for the methods planned.

Automated drilling equipment that

records down-pressure, torque, and

depth can effectively communicate

drilling conditions in real time without

the delays and labor required for hand

logging. Have a plan of action to adapt

to changing conditions. For example, if

it is anticipated to grout small fractures,

and large cavities are discovered during

drilling the notifications to the engineer

and owner, must be immediate so that

an evaluation can be made as to whether

and how to proceed with handling this

new condition.

The drilling should attempt, to the

extent practical, to assess whether

voids in rock are soil filled and con-

tinuous. The continuity of voids is

often observable as lost circulation of

drilling fluid (air or water) appearing in

adjacent holes and should be recorded

and reported where it occurs. The con-

ditions in each hole should be evalu-

ated by the project engineer prior to the

grouting. A hole should never be termi-

nated in a void without direction from

the engineer, since it may be desirable

to deepen the hole and it will shave cost

to do this while the rig is already pres-

ent than to have to move it back into

place later.

In karst it is not uncommon to en-

counter rock drops that bind the drill

casing or for the casing to become

wedged due to drift of the drill string

on sloping rock surfaces. In these in-

stances, it may be of value to change

the orientation of the boreholes. The

boreholes should be oriented to be as

close to perpendicular to the feature

surfaces as possible. This can reduce

the potential for casing drift and make

it less likely for sections of rock to fall

at an angle to the drill string.

Managing the Grouting

The actual injection of the grout may

or may not achieve the desired result.

It is essential to closely monitor and

interpret the observed behaviors during

grouting to assess whether the grouting

is likely to meet the project objective.

While the cost for engineering

observation during the grouting is

often considered excessive, the cost for

a failure of the grouting or for later re-

grouting the site will be considerably

higher. The engineer in the field must

have a clear understanding of the

subsurface conditions, what the grout is

expected to do in the ground, and what

the overall objective of the grouting is,

to be able to make good decisions.

Monitoring of the grout properties

is essential to interpreting the grouting

records. The viscosity, and thixotropy

of the grout will directly determine

grout behavior. Low viscosity grouts

will penetrate fine openings and travel

farther than higher viscosity or limited

mobility grouts under the same pres-

sures and rates of injection. The grout

material properties, both wet and in the

hardened state, must be consistent with

the planned injection procedures and

controls, and with the final objective of

the grouting.

Refusal criteria must be established

to permit effective grouting while

maintaining adequate control. The dan-

ger of causing damage with the grout-

ing increases directly with the volume

and pressure of grout injected. So,

refusal criteria should include provi-

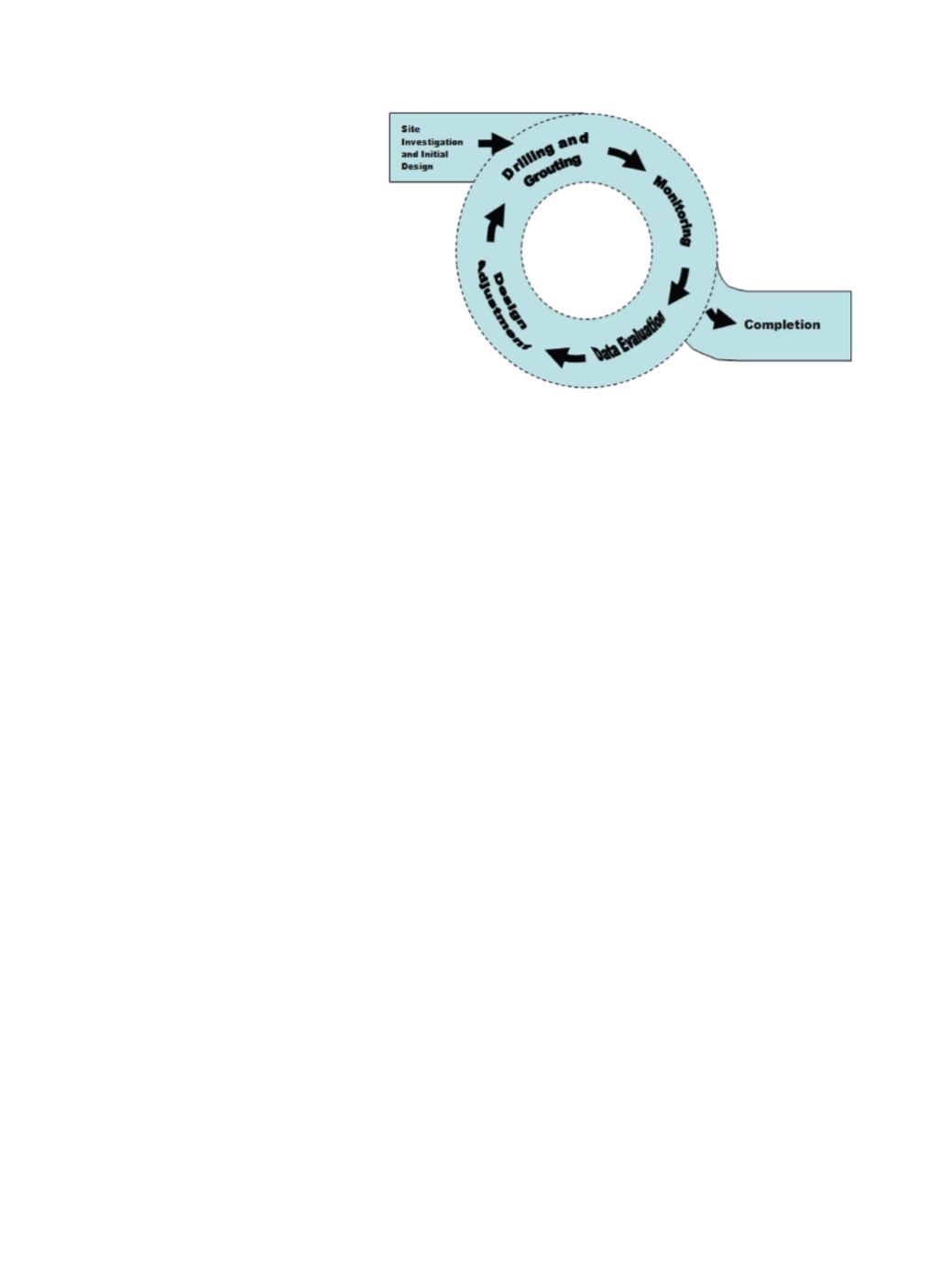

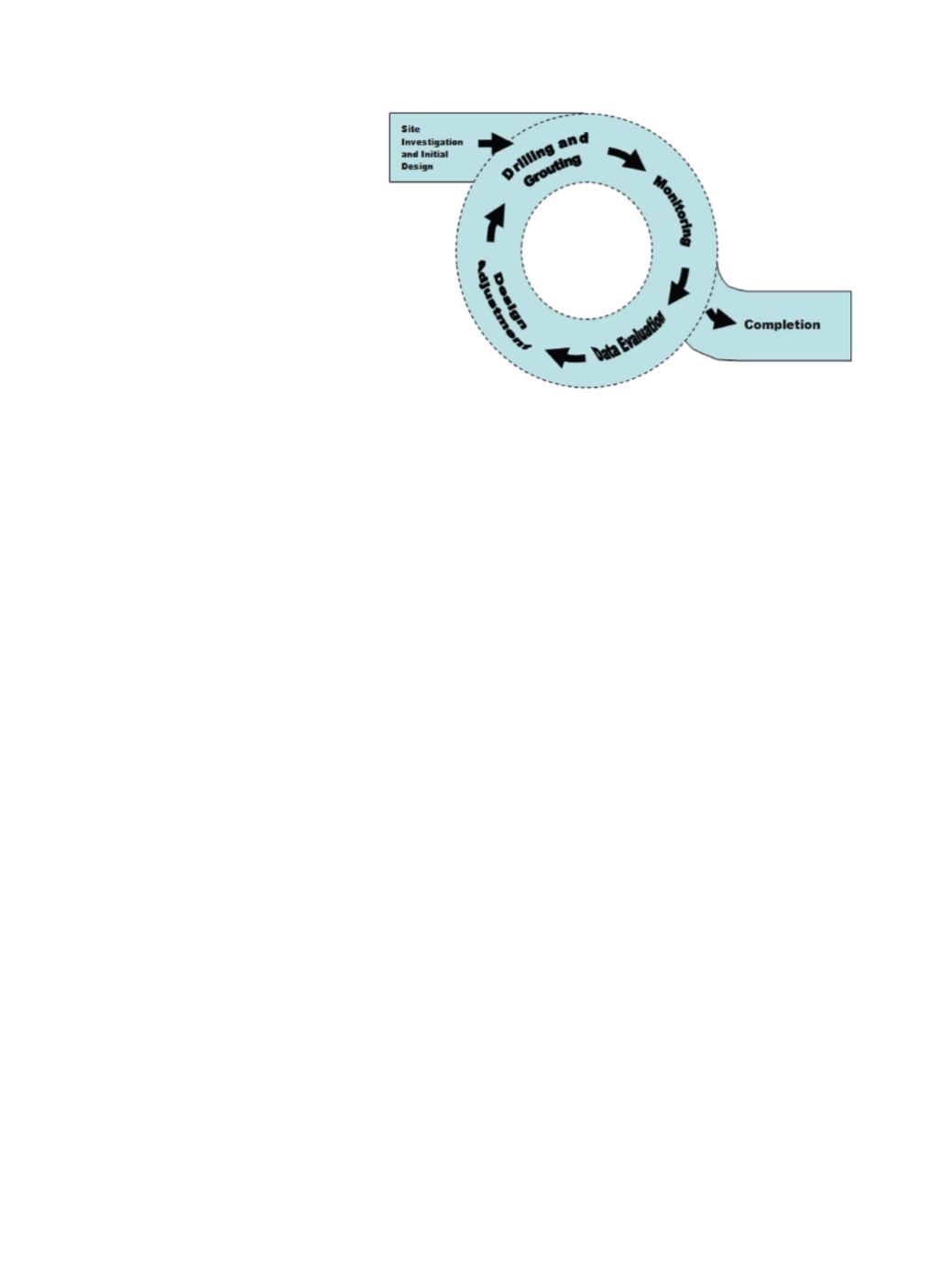

Figure 8. Grouting in Karst Design Cycle.