Geotechnical News • December 2017

35

GEO-INTEREST

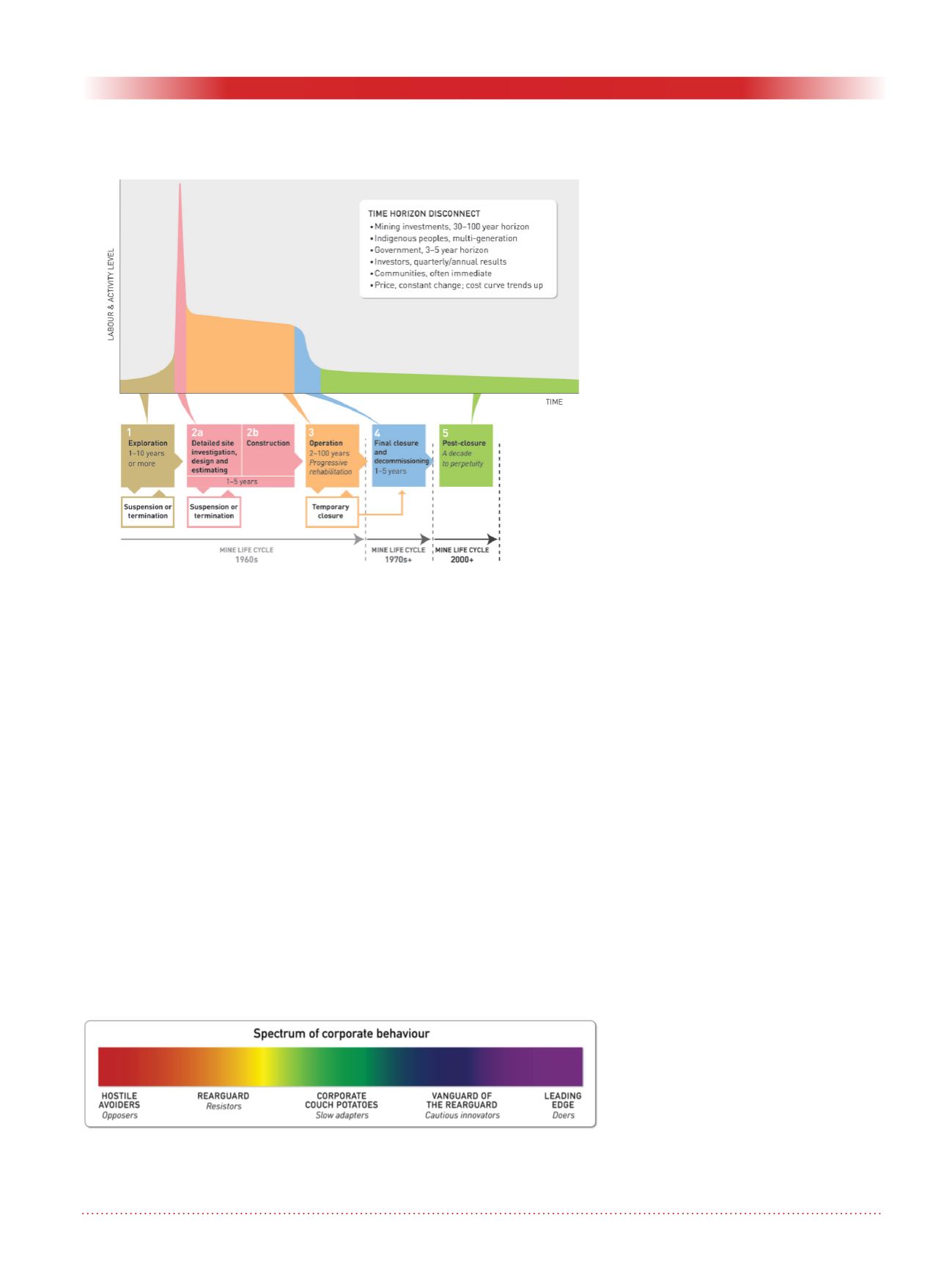

Seeing the full project life-cycle

A particularly important challenge

plagues the mining industry. Figure 2

shows the mine life cycle by phases

and level of activity. Note the lower

time line plot. Until the late 1960s,

little attention was given by com-

panies or governments beyond the

operations phase. In the 1970s, closure

came into the industry and regulators

radar. Only about the year 2000 was

the importance of the post-closure

phase recognized. Note also the box

on the upper right which lists the time

horizons of typical concern for various

interests and how they vary signifi-

cantly.

Very few interests see and address the

mine life cycle as a “whole” continu-

ing process. Within a company, explo-

ration, construction, operation, closure

and post-closure are undertaken by

different teams of employees. Within

government, a whole-project regula-

tory perspective simply doesn’t exist.

And amongst civil society organiza-

tions, almost always the focus is on

a crisis or a single-point issue (like

licencing). Only rarely is the idea of

a full life-cycle used as the basis of

design courses in academia. Lack-

ing such integrative thinking, it is not

surprising that mine designs are weak

on long-term integration. Though

ideas of design for closure were first

introduced by leading edge thinkers in

the 1980s, design and implementation

for closure is only now entering the

mainstream of thinking.

Actions for the Geotechnical

Engineer

In summary, contemporary society

needs the commodities produced by

mining but carries little understanding

of what it takes to produce those com-

modities. At the same time, society

continues to call for an industry that

seeks and attains a positive contribu-

tion to both human and ecosystem

well-being.

In fact, what we find is an industry

that:

1. consists of many components with

companies that are tiny to huge

and characterized by a broad varia-

tion in objectives, interests and

behaviours;

2. operates across many cultures, but

does not always demonstrate effec-

tive intercultural communications;

3. is often (but not always) distrusted

and criticized for taking too much,

giving too little, and expressing

good intentions while not follow-

ing through with performance on

the ground;

4. is regulated by a system of gov-

ernance that is equally complex,

disjointed, and not carrying the

respect of either industry or the

public.

In the high-level maze described

above, what does this mean for the

geotechnical engineer and geoscientist

in terms of their day-to-day practice?

The following five concrete actions

will contribute greatly to strengthening

the alignment between society’s values

and industry practices.

Action 1. Champion the long term.

Those trained in the geosci-

ences understand natural

process in terms of geologi-

cal time; you understand the

long term and need to be its

champion amongst others

who don’t, be they technical

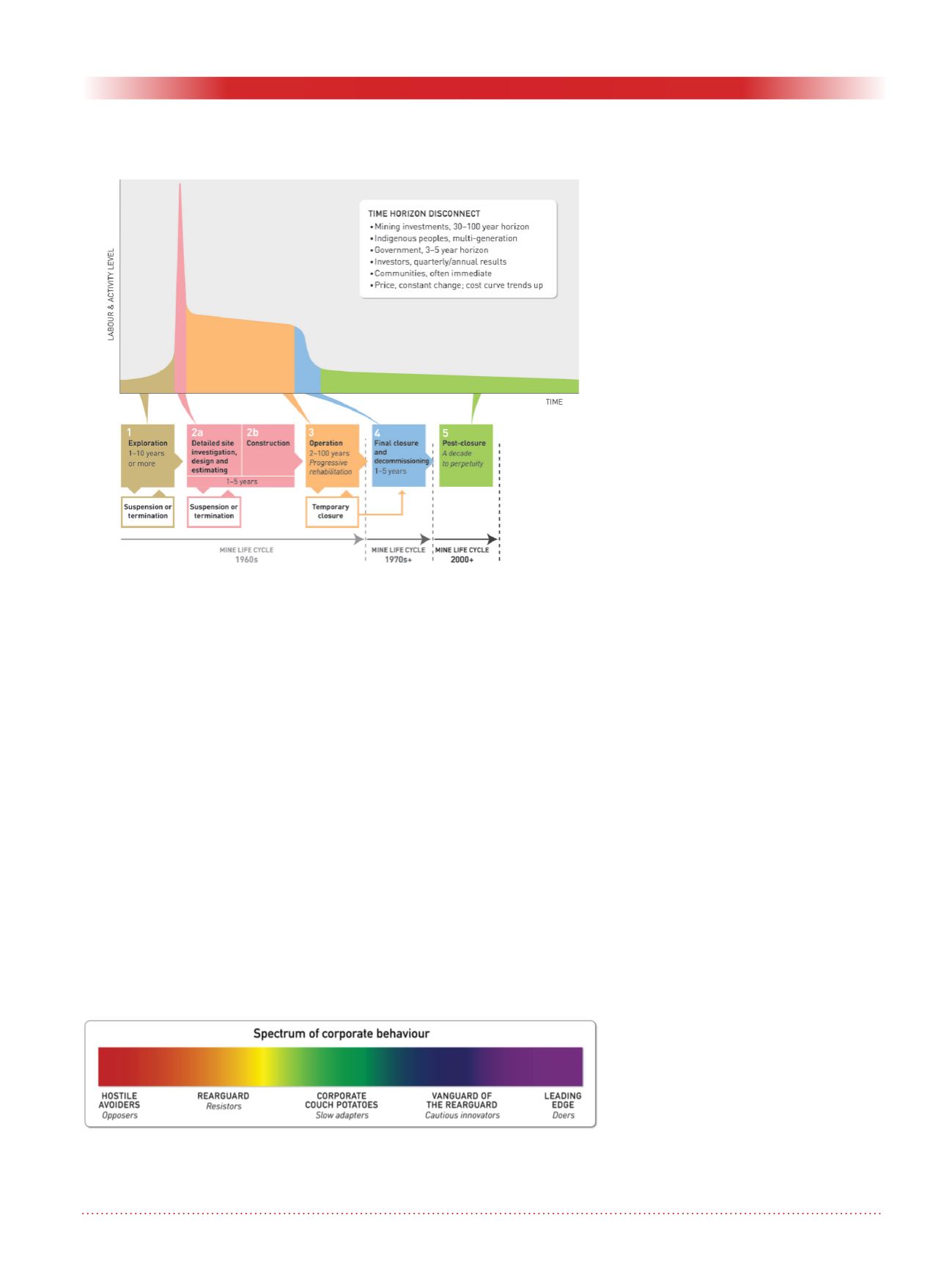

Figure 1. Spectrum of corporate behaviour. (After John Gadsby (2000),

Hodge 2011; personal communication, ICMM 2012).

Figure 2.The mine project life cycle by activity level; approximate dates when

the mining industry and regulatory perspective expanded to include each

phase; time horizon disconnects between interests. NRTEE, 1993.