44

Geotechnical News •March 2015

WASTE GEOTECHNICS

mines located in the southern part of

the country may be subject to annual

rainfalls of over two meters, a large

portion of mines are concentrated in

the north, which is extremely arid. In

the Atacama Desert, which occupies

much of the northern territory, average

annual precipitation can be less than 2

mm, while potential evaporation soars.

Sites of such extreme aridity can bring

unexpected benefits for closure design.

At least in theory, small quantities of

contact water can potentially elimi-

nate or dramatically reduce acid rock

drainage (ARD), by the reduction or

elimination of one of the three ele-

ments needed for its generation (the

others being oxygen and a waste with

the potential to generate ARD).

At some sites, contact water quanti-

ties are so small in comparison with

evaporation rates, that a strong case

can be made to eliminate many com-

mon control measures. Unfortunately

for the engineer, the closure design is

rarely so simple. Many of the arid sites

are subject to occasional, but sig-

nificant, rainfall or snowmelt events.

Due to limited data, it can be difficult

or impossible to characterize to an

adequate confidence level what is the

“real” 1-in-100 year or 1-in-1000 year

event. To dimension the difficulty,

consider that having 90% confidence

in just a 25 year storm requires 59

years of precipitation data – a quan-

tity of data that would be considered

excellent for many sites in Chile. The

difficulty in correctly estimating the

intensity of the low frequency storm

events results in a number of design

challenges. Water diversion structures

that have been sized based on con-

ventional precipitation estimates can

result in the construction of immense

structures in the desert that will remain

dry for years or decades – or possibly

even in perpetuity, given the uncer-

tainties in the estimation of the design

storms. On the other hand, there is

little expectation that more innovative

(and potentially more realistic) esti-

mates will be accepted by the approv-

ing authorities.

In theory, potentially acid generating

waste rock could sit with oxidation

products developing on the surface of

the rock for years, and these products

would then be flushed by the storm

event. Adequately characterizing the

risks associated with such events

ideally requires consideration of a

range of issues, including statistically

defined water balances, reaction rates,

and dilution potentials. Receptors

must also be figured in the equation.

Many sites benefit from their extreme

remoteness from inhabited areas.

Groundwater resources are often iso-

lated as well, with water table depths

below ground surface of 90 meters

or more, protected in varying degrees

by bedrock, dense desert soils, and a

powerful evaporative regime. On the

other hand, unique and sometimes

fragile desert environments may come

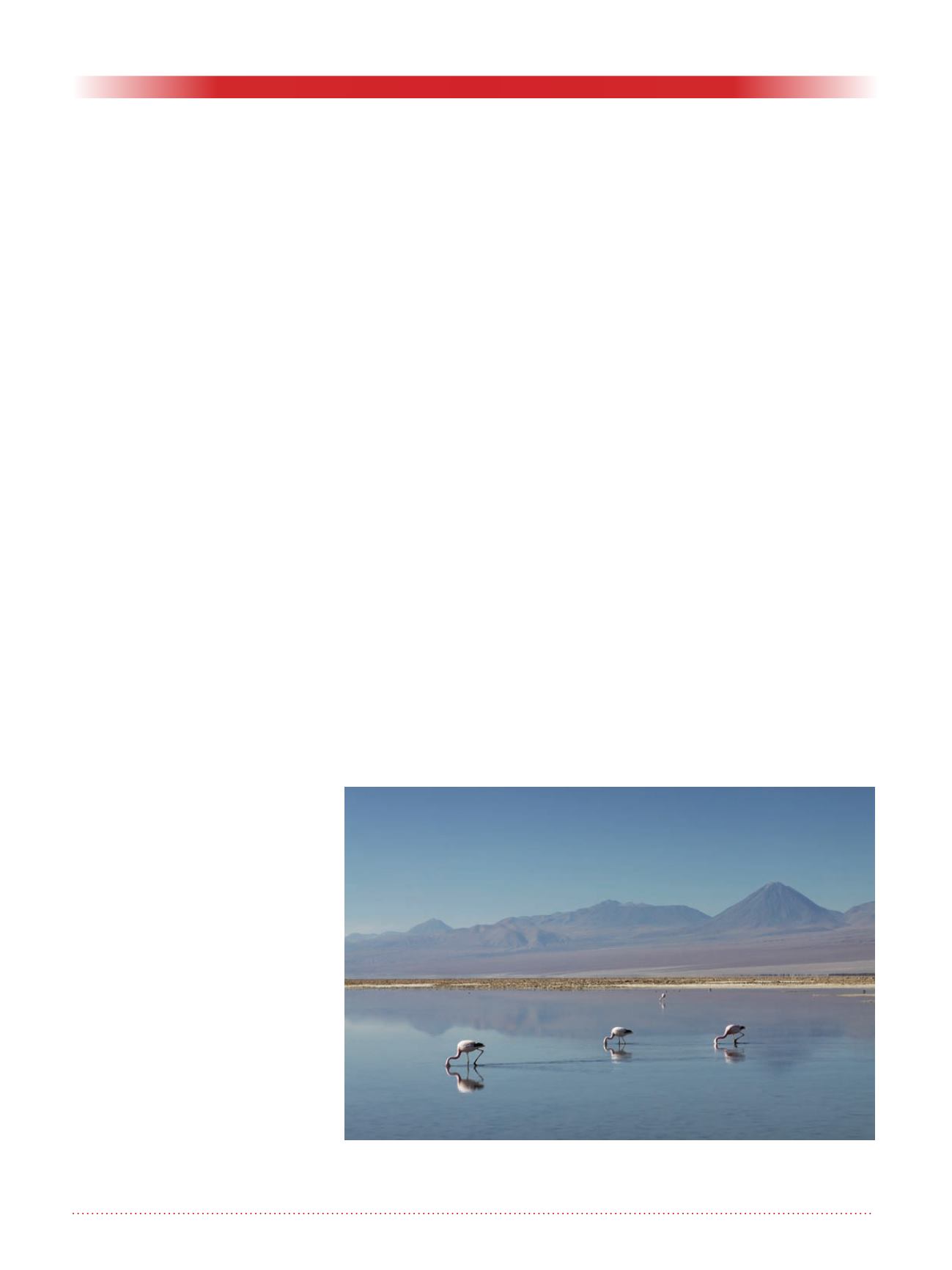

into play. A common and particularly

sensitive case is the salar environment,

where all discharges from a watershed

drain to an isolated internal evapora-

tion point, the salar. These discharge

points are delicate ecosystems, home

to a variety of species including the

famous flamingos, or the deer-like

vicuñas (see Photo 2).

Even where ARD issues are not a

concern, the aridity can create other

issues, particularly the generation of

dust. Waste rock dumps tend to be

relatively immune to this problem,

at least in the long term. The range

of grain sizes present in a waste rock

dump can be expected to provide con-

siderable protection form the ongoing

generation of dust through the forma-

tion of a “desert pavement”, a process

in which finer particles are scoured

away by the wind, leaving a resistant

surface of the particles too large to be

moved.

On the other hand, the closure of any

tailings facility requires a site-specific

evaluation of dust generation post-

closure. Due to the relatively fine

and uniform size of many tailings,

they may generate nuisance dust for

decades or even hundreds of years

after closure. While to a foreigner the

concern of Chilean regulators over

dust generation may seem exagger-

ated, a quick visit to Chañaral, a

coastal town located approximately

800 km north of Santiago can provide

some rapid context. Historic marine

disposal of tailings in the bay just

north of this community has resulted

Photo 2. A typical salar environment. (

/

by-sa/3.0/deed.en).