32

Geotechnical News March 2011

GEOTECHNICAL INSTRUMENTATION NEWS

intrados and one at the extrados in cir-

cumferential direction. The four sec-

tions are equally spaced around the

ring circumference. In order to esti-

mate axial force and bending moment

in the permanent lining of the Buttoli

tunnel, a cross section was provided

with five pairs of strain gauges, equally

distributed along the lining: a pair for

each side, one at the crown and other

two intermediate points. The invert was

not instrumented. In both the example

cases, the strain gauges were welded to

steel bars.

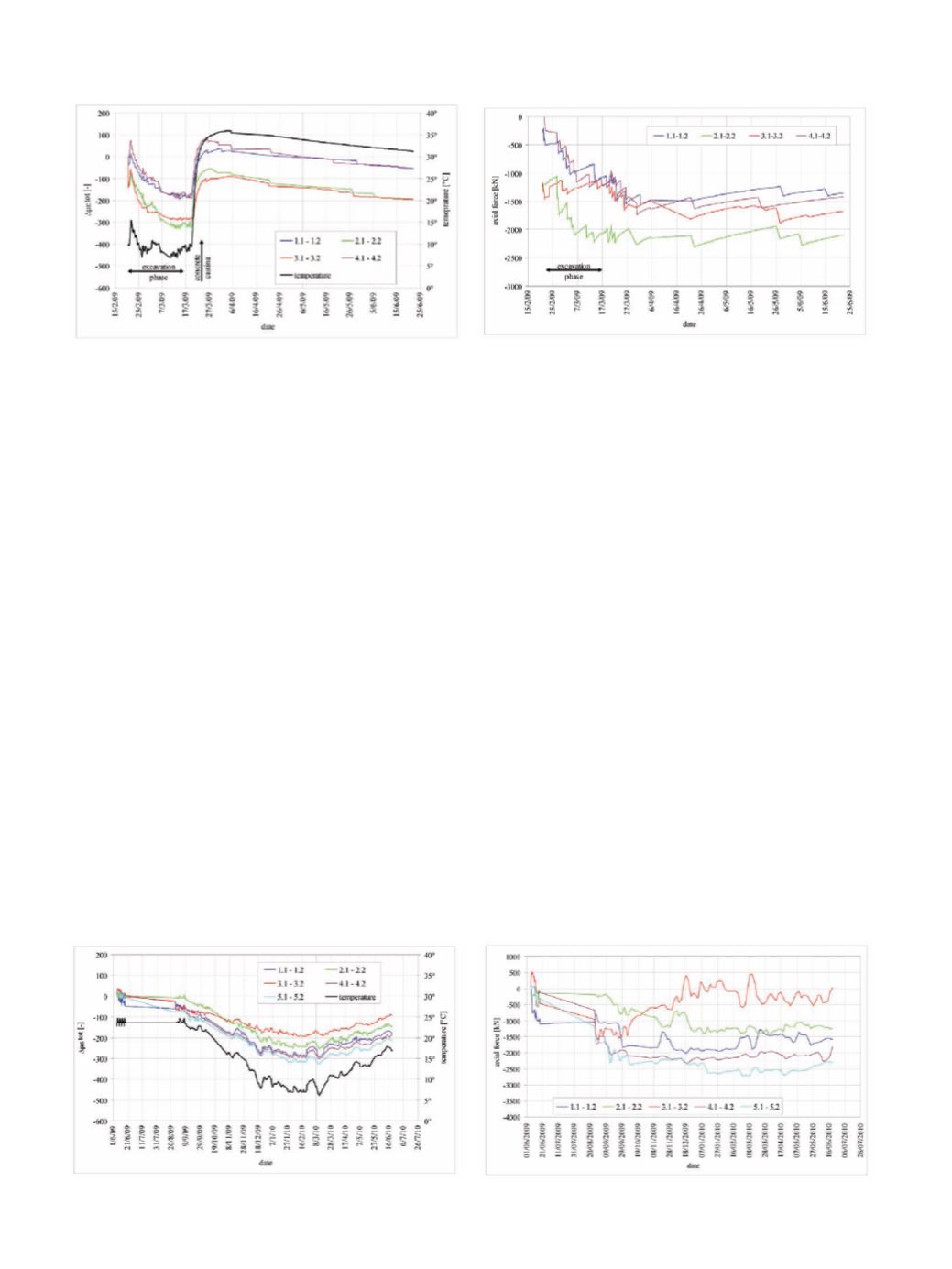

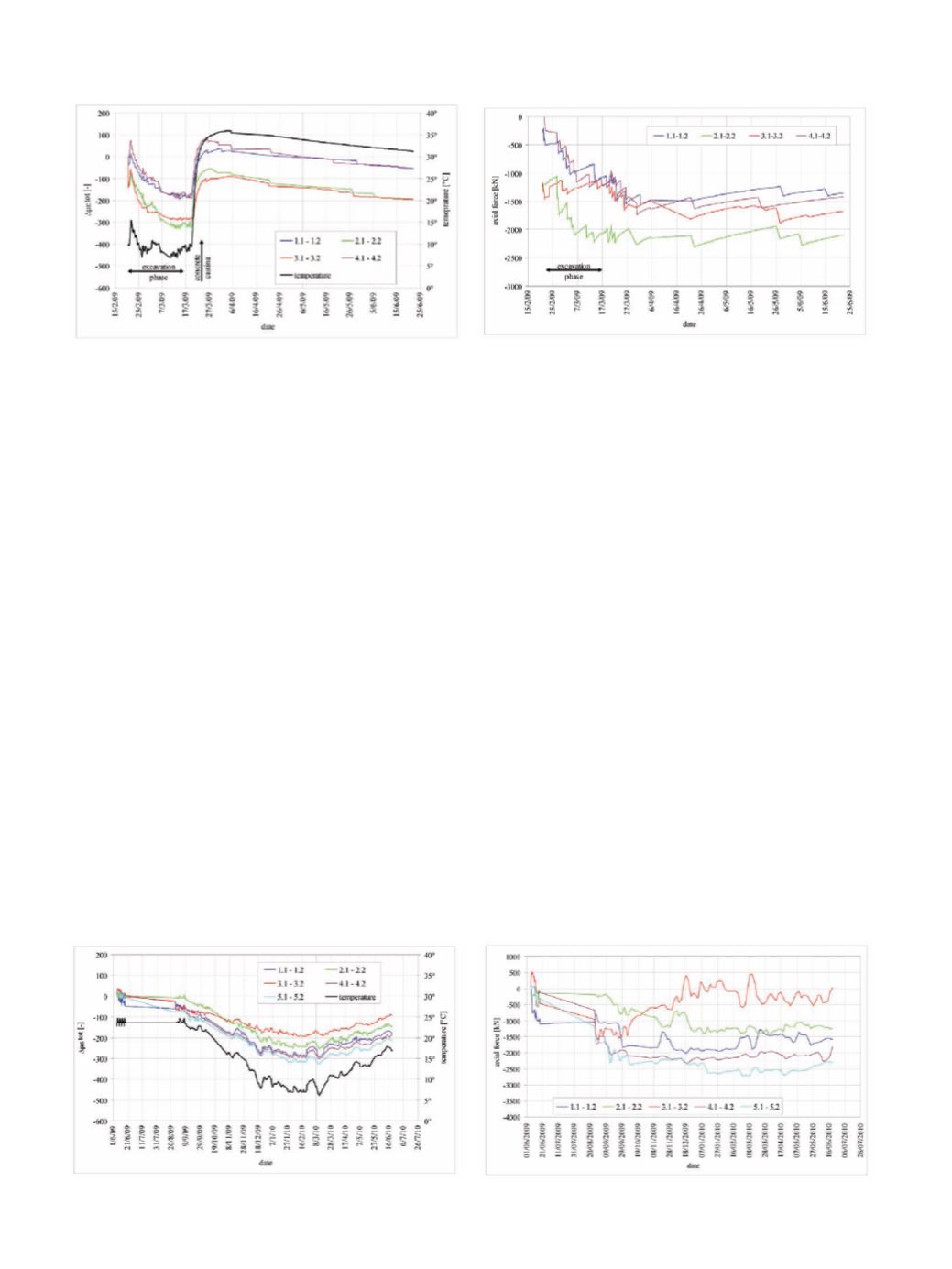

In the following figures, the cor-

rected measured total strains, averaged

in each instrumented section between

extrados and intrados, and the corre-

sponding axial forces, computed by

the proposed procedure, are shown for

both the ring beam (

Figure 2

a, 2b) and

the tunnelling example (

Figure 3

a, 3b).

Each curve refers to a pair of strain

gauges; as for the tunnelling example,

1.1-1.2 and 5.1-5.2 correspond to the

pairs of strain gauges placed on the

left and right sides of the tunnel lining,

3.1-3.2 to the one placed at the crown

and the remaining ones to the two in-

termediate points. In the total strain

versus time figures, temperature inside

the concrete is also plotted. In

Figure

2

a, the effect of the temperature rise

due to concrete casting on the strain

values is clear, whereas, in a similar

way, the effect of seasonal temperature

variation on the concrete strain can be

seen in

Figure 3

a. The maximum val-

ues of axial force derived by the mea-

surements turned out to be in both case

studies within the design values: in the

first case, the measured value is almost

70 % of the design one, whereas in the

second case the maximum measured

value is equal to 65% of the design val-

ue. Such differences can be explained

by precautionary assumptions adopted

in the design phase.

The importance of applying the cor-

rect conversion procedure is shown in

Tables 1 and 2. For each of the two

considered examples, the final axial

forces computed by the proposed pro-

cedure (N1) are compared to the ones

derived by disregarding respectively:

• N2: shrinkage and aging (i.e. chang-

ing Young’s modulus with time);

• N3: creep and aging;

• N4: creep and shrinkage;

• N5: considering concrete as simply

an elastic material (i.e. disregard-

ing all time-dependent effects).

As is clear by comparison between

N1 and N5, if the conversion procedure

is too simplified, the stresses can be

overestimated by a factor of nearly six.

Conclusions

In order to obtain reliable estimates

of stress by installing strain gauges

embedded in concrete structures or

welded to reinforcement bars, a proper

conversion procedure must be adopted.

The proposed procedure takes into

account the complex behaviour of

concrete by considering the effect of

shrinkage, creep strain and hardening.

Such a procedure can be easily

implemented by an Excel spreadsheet

and a Visual Basic routine. As shown

by the examples, the proposed

procedure leads to results that can be

compared to the design estimations,

whereas adopting too simplified a

Figure 2a. Ring beam - Measured in strain vs time.

Figure 2b. Ring beam – Computed axial force vs time.

Figure 3a. Tunnel lining – Measured strain vs time.

Figure 3b. Tunnel lining – Computed axial force vs time.