Geotechnical News • December 2018

31

GEOHAZARDS

acceptability, specific hazards related

to debris flows and landslide dams

related to volcanism. The proceedings

remain on my bookshelf today. Since

1992, the Canadian understanding of

thematic elements widely discussed

in the first conference has grown dra-

matically. Some key events (from the

writer’s perspective) in the history of

this growth include:

• 1994: The Kwun Lung Lau land-

slide in Hong Kong (HK) mate-

rially affected the Slope Safety

System employed by HK. While

not widely known in Canada at

the time, increased effort to reduce

risk including use of FN curves

and establishing tolerable risk

limits, would ultimately guide

Canadian practice.

• 1995: The Forest Practices Code

was enacted in British Columbia.

This act (and subsequent pro-

grams) pushed the assessment

and management of geohazards

(landslides, streams, flooding,

erosion) into legislation and cre-

ated the catalyst that gave rise to a

new cohort of active scientists and

engineers investigating and ana-

lyzing data, delivering geohazards

programs, and creating more than

15 years of related literature.

• 1996: The US Transportation

Research Board released Special

Report 247: Landslides – Investi-

gation and Mitigation. Building on

previous work beginning in 1972,

this volume became a definitive

tool for a common understanding

about landslides (including an up-

date to the Varnes classification).

• 1997: The workshop on Landslide

Risk Assessment in Honolulu

Hawaii. This landmark workshop

brought together multiple special-

ists to understand how to use new

tools in hazard and risk assess-

ment.

• 1997: Conrad Siding debris flow in

BC derailed a train and caused 22

million dollars in damage.

• 2002: Zymoetz River rock slide

debris flow in BC ruptured a

pipeline, triggered a forest fire and

dammed the Zymoetz river. 300

people were evacuated, and the

cost was estimated at 33 million

dollars.

• 2005: Berkley Escarpment land-

slide in the District of North

Vancouver (DNV) caused the

evacuation of 300 people, the loss

of 2 homes and cost over four

million dollars. More importantly,

DNV became the first community

in Canada to fully engage in a

landslide risk assessment program

and develop tolerability thresholds

for new and existing development

(based largely on the HK work).

• 2007: The Intergovernmental Panel

on Climate Change published and

won a Nobel Peace Prize for its

Forth Assessment Report. Almost

two decades after its inception, the

focus on mitigation and adaptation

garnered widespread acceptance

and caused a sea-change in the un-

derstanding of a dynamic vs. static

earth. Widespread acceptance led

to flood protection works and the

notion of building resilient com-

munities across North America.

• 2010: Mount Meager landslide oc-

curred (from the complex identi-

fied as problematic in Geohazards

1) becoming Canada’s biggest

historical landslide at 52 mil-

lion square meters. 1,500 people

evacuated due to potential for

damage because of a landslide

dam outburst flood associated with

the landslide. Total cost was ten

million dollars. New updates to the

landslide have been acquired with

structure from motion technology.

• 2010: Saint Jude lateral spread in

sensitive marine clays, Quebec.

At 6.5 million dollars of damage,

this landslide also reminded the

community about the considerable

dangers of spreads, compound

landslides and flow slides. This

landslide type is typical of the

marine clays in Quebec, but also

reminiscent of the weak shales

and glaciolacustrine soils in the

Interior Plains (where, perhaps

surprisingly, the most money is

currently spent on landslide assess-

ment, monitoring and mitigation).

Improved analytical power also

means that these landslides are

better understood than ever before.

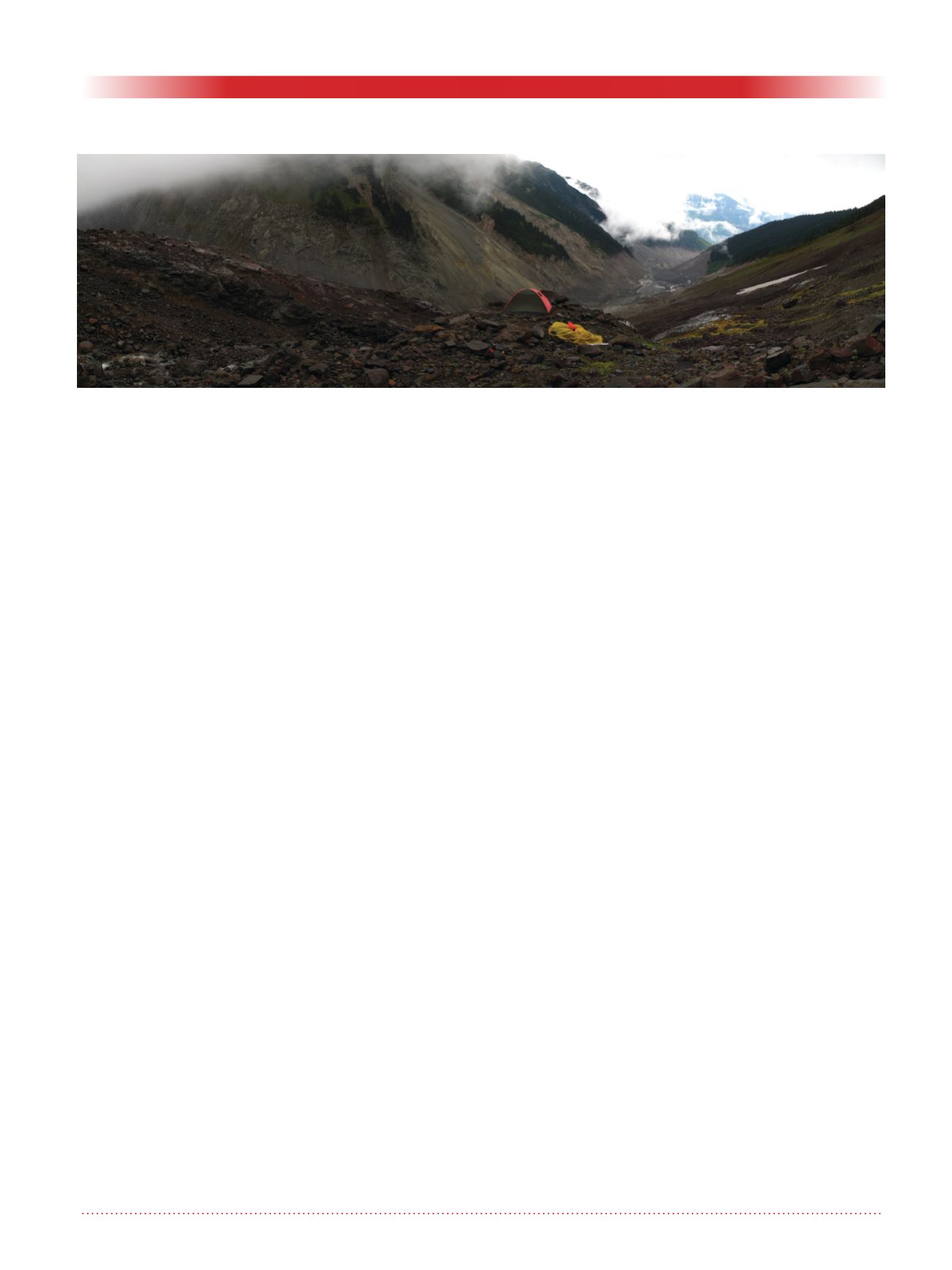

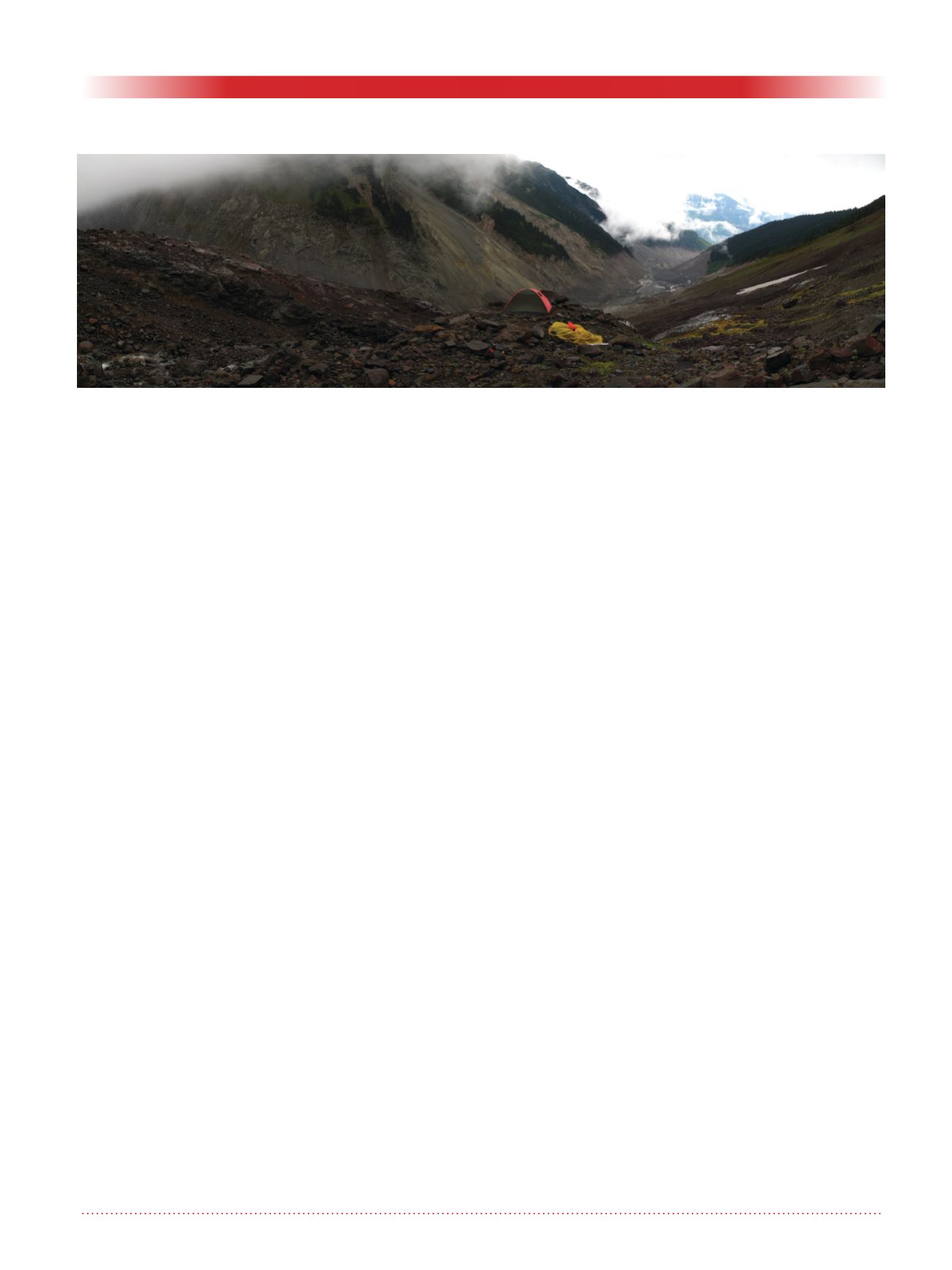

Figure 2. Room with a view – looking out at the devastation caused by the 2010 Mount Meager landslide

(photo by R. Guthrie).